|

There are many ways to adapt the popular card game, "Apples to Apples" to the Latin classroom. This particular variation besides being a very big hit in my Latin II class was also very easy to assemble.

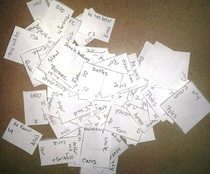

If you haven't played the game or it's rated "R" variant, "Cards Against Humanity," you need two types of cards - people cards and descriptive cards. In my variation, the people were celebrities my students knew and the descriptive cards are phrases in Latin the students will understand. For a group of 5 players, you need about 100 index cards with celebrities and about 20 descriptive phrases which can be written on the board. Step I: Generate the list of names. Tell your students to write names of well-known people on your class white board or have everyone contribute a person to a shared document or one that you have projected on the board. Have students reflect on the list - it should be a mix of cartoon characters, literary characters, people from history, super heroes, movie, pop and Youtube stars. I don't let them add names of people in the school - that could quickly turn cruel. As the list is generated, make sure that everyone knows the characters on the board and delete those that only a few students are familiar with. Step II: Then when you have a list of about 100, hand out index cards to the class and divide the evenly by the number of students in the room. For example, if you have 20 students, each student is responsible for 4 celebrities. Also with 20 students, you would need 5 groups of 4 students each so each student should write their five celebrities on four different index cards so that you can generate 4 decks of cards. It helps if you can hand out colored index cards so each deck can be its own color but its not necessary. Step I and II generally takes about 30 minutes. Collect the decks, put rubber bands around them and announce to the class that you will play this game later. Step III: Now you need to generate some Latin phrases that could apply to these celebrities. There are many different possibilities here. This is an excellent activity for practicing superlative and comparative adjectives, partitive genitive and even optative subjunctive. Below I have some examples: Rex mundi Dux hominum Amor meae vitae Laborat nocte Nemo eum amat Intelligentior quam Julius Caesar pulcherrima mulier Utinam adesset Utinam essem coniunx Utinam esset mortuus Clamat semper You don't need to write these on index cards although you can if you want and have the time to do so. Step IV: Playing the game - Put the students in groups of four and give each group one of the decks that you generated. In each group, have one student deal out five cards to all players in the group. Each group should choose a "leader." This role will rotate each round. Now the teacher writes one of the phrases on the board. Each student looks at the cards in their hand and decides who of the cards they have best exemplifies that phrase. They then give their card to the "leader" who reads them all aloud and decides who they think best fits the phrase. The student who had that card gets a point. Now the student to the right is the new leader and the process repeats. Each student should take a new card from the deck to the replace the one they played. The teacher writes a new phrase on the board. Students again check to see which card best fits the new phrase, hands it to the new leader who makes the decision and so on. Tips to Make this Game Work

1 Comment

Spoons! is an old card game but has been used in language learning for many years. My student teacher, Alex Simrell, taught it to me last year and I have repeated it several times with my other classes. I have since learned that both the Spanish and Mandarin teachers were already using this game in their classes. Basically, I am the last to know. Spoons works well for both simple grammar and vocabulary retention. To play a game of spoons, you need to make a set of cards that has between 48-52 cards in the deck for each group of players. Students are going to be collecting either two pairs, or three or four cards that clearly go together. For this reason, you can make a deck that has the following:

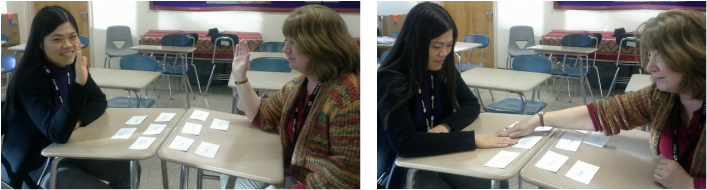

Divide students into groups of 3-5 players per group. Give each group a deck of cards and one less spoon then there are players in the group. For example, a group of four students would have three spoons. Now, if the goal is for students to make groups of three, then each student should be dealt three cards. If the goal is for students to make groups of four cards or two pairs, then students should receive four cards. Now, the person to the right of the dealer draws one card from the remaining pile and then passes a card that he or she does not want to the next person. This person then takes the card and either keeps it and passes another card to the next person or passes that card. Everyone should have the same number of cards in their hand that they started with. While the passing of the cards is taking place, the spoons should be placed in the center of the circle in the manner pictured above. Passing the cards should happen quickly. Everyone should be simultaneously recieving and passing a card. Students should be looking to make 2 pairs or three of a kind or four pairs. So let's say for example, you are playing with a deck that has principal parts. A student who has cards that say dico, dixi, facere and cepi should pass either facere or cepi while hoping to receive dicere and dictum. Now once a person has gotten four of a kind ( if you are using principle parts), he or she grabs one of the spoons from the center. Now everyone else must grab a spoon as well (even though they don't yet have all their cards matched.) The person who didn't grab a spoon in time gets an S. Second time, they get a P. (You are spelling out SPOON here). Now simply repeat the process. Collect the cards, replace the spoons in the center, shuffle the cards and redeal and restart. This game can be played for about 5 rounds (about 20 minutes) before it gets old. This is another incredibly simple, incredibly successful game that I've been playing with students of all ages. Linda Kordas, retired teacher from Concord, New Hampshire taught it to me. To play this game, students need a set of on flashcards (about 15-20 words). The Latin word should be on one side and the meaning on the other. The words need to be fairly large and legible. For more information on how to make flashcards a regular part of your instruction, see the Cards of Flash on Beginning Activities. This game is best played after students have had some time to practice with the flashcards in partners. They need to have some familiarity with the words for this to work although they will know them a great deal better after this game. To begin, instruct the partners to put their desks end to end and spread one set of flashcards - whoever has the neater set, between both desks. Here is a helpful picture below. In the first picture, the Mandarin teacher and myself are modeling the set-up. One set of flashcards has been evenly divided between two desks facing each other with the Latin side up. I usually play with about 15-20 cards but these were all I could find in the recycling bin at the time I was staging our demo. We have our arms bent because we are also demonstrating what I call the "Official Slap and Grab Position." I tell students that it looks like you are about to swear an oath. They may not hover their hand over the cards. Now the teacher calls out one of the words in English and the students find the card, slap it (or rather touch it or their hands will be stinging), turn it over to make sure that it was correct, and then pull the card out of play. If a student has slapped the wrong card, he or she must wait 3 seconds before slapping another card. Students can slap cards on both desks. You continue calling out words until there are only two left. Then ask students to count the number of cards they have won and set up for the next round. I usually play three rounds of this game. The first two rounds are Latin to English and the last round, I ask students to put the English side up and I say the Latin word.

Tips to Make this Game Work:

This game is another recent addition to my repertoire. Like several other games I have described, it was plucked from the internet by my sharp-eyed colleague, Jill Jackson, who has a real knack for finding stuff that works. If you are lucky or unlucky enough to teach other subjects in addition to Latin, you will find that you can easily adapt this game to just about any subject and any level. It's that flexible as well as wildly entertaining. Pre-Game Preparation: Put your class into groups of 3-5 students. Four is really the optimum number here, if that is possible. Homogeneous grouping is best for this game since each students will be playing against other students in the group. Acquire one six-sided die for each group and a tray to roll the die into. Create 2 worksheets: each with enough problems that can be done in about 20 minutes. It helps if the questions get progressively more difficult and require definitive but short answers. How to Play: Students sit together in their group. Each student in the group has a copy of the worksheet. In this game, students compete against each other. Each student in the group takes turns rolling the die into the tray. When one student rolls a "6," then he or she stops rolling and starts doing the worksheet as fast as he or she can. The other students continue to pass the die and when one of them rolls a "6", then the student doing the worksheet must stop immediately and the student who most recently rolled a "6" starts doing the worksheet. Again, the remaining students continue to pass the die, each one of them taking turns rolling the die until another students rolls a six. Once again, the student doing the worksheet stops and the new student starts work. The goal of the game is to be the first one in the group to finish the worksheet correctly. Once a student has completed the worksheet, he or she brings it to the teacher who anoints him or her the winner if it is correct. However, if there are mistakes, the teacher highlights the mistakes. Now the student goes back to the group and continues to roll. When he or she rolls a six, now they correct the worksheet. Tips to Make this Game Work:

This card game, unlike the others in this blog uses actual playing cards. Also unlike the others, it is a relatively new addition to my card game repertoire. I learned it from Jill Jackson, the resourceful Spanish teacher at my school who also told me about Latin basketball and several other great activities on this site. It worked very well in my class; rules and play are such that I see no reason why it won't continue to work well for many levels. This game, like Stercus works well to help students learn small chunks of material, - vocabulary or phrases of any level. It is best played in small groups of two or three students. What you need: You need one deck of regular playing cards for each group of students. Collect up all the old decks of playing cards you have lying around your house and then go to the Dollar Store or the local Job Lot for more. You also need a worksheet divided into four columns - hearts, diamonds, spades and clubs. List each of the cards along the left-hand column and square it off to create a grid. In each square, there should be a word or phrase that you want students to translate or say in Latin. Below is a picture of one that I created. The full size version of this is also in the Card and Board Game Google drive folder.  For words written in English, students must say the Latin and vice versa. I wrote this worksheet to help students practice prepositions and ablative endings but just about any small chunk of information can be placed in the grid. Pre-Game Preparation: Divide your class into groups of two or three. Give each group a deck of cards and each person one of these worksheets. You may also want to create and hand out a key - one per group. It's not always necessary to create a key because often the students can come up with the correct answer by discussing it among themselves. How to Play: One student deals out all the cards to the players in their group. Then, simultaneously, like the card game, War, all the players turn over a card. The student with the highest card has to find the question on the grid that corresponds to their card and say the correct answer. The worksheet in the drive was used for preposition practice. If the phrase is in English, then students needed to say the Latin and vice versa. If he or she answer correctly, then they get all the cards. If he or she gets the answer wrong, then the person with the next highest card gets to answer and subsequently gets all the cards if they get it correct. If this person gets it wrong , then the person with the third highest card has a shot. If no one in the group gets the answer right, then everyone turns over another card on top of the one that they played. Again, the person who turned over the highest card answers the question. If he or she gets it right, then they take all the cards. Play continues until one player is out of cards. The winner is the player with the most cards. Sometimes in the copy room or the faculty lounge, a teacher will ask me conversationally what I'm doing with my class today. If the answer is, "we're going to play a card game," I feel the immediate need to justify and explain it - "It's a Latin card game, to teach case endings, verbs etc." The phrase "playing a card game" sounds frivolous . I worry that what my colleague heard was "I don't feel like teaching this class so I'm just going to waste time."

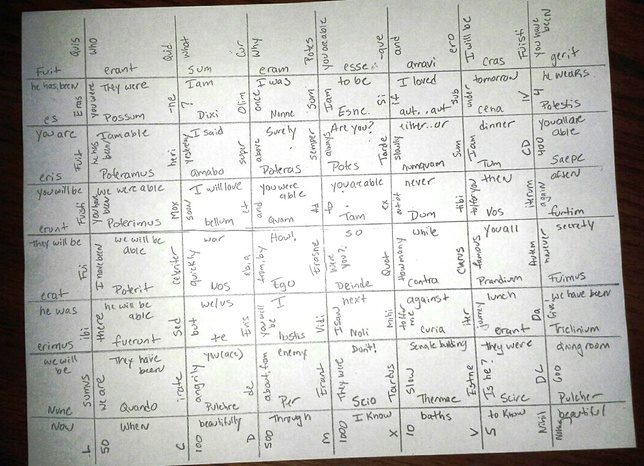

Of course nothing could be farther from the truth. Card games are very instructive. Even better is that after the groups have been made, and the rules explained, they don't require that you lead the activity. You can observe, monitor, or if your class is self-sufficient, you can remove yourself entirely and correct papers, write lesson plans and do the thousand other things you generally never have enough time to do. While this sounds blasphemous, it is important that the teacher not be the center of instruction. Students need to be active participants rather than passive receptors of learning if any of it is going to stick. Teachers need to step back and recharge their batteries. Card and board games provide opportunities for both of these things to happen. It's a win-win situation all around. So if the term "card game" makes you nervous, call it an "interactive student-centered cooperative learning activity." Perhaps someday I'll say this myself when someone asks me what I'm doing with my class - unlikely though. I've got enough educational jargon in my life already. Anyone who is truly concerned should just come by - we'll deal you in. Vocabulary puzzles are another idea, like Stercus that have many different originators. They are another way to diversify instruction and learning. It is a quieter, often more intense activity and makes a good contrast to some of the kinetic games that can be used to accomplish the same things. To make a vocabulary puzzle, you take a sheet of 8 x 11 paper and fold it in half 6x. That's right - six times . When you are done, you will have a folded piece of paper, the size of a postage stamp. When you unfold it, you will get a grid that's 8x8. Then take a ruler and carefully mark out the grid along the folds. Now, along each rectangular border, write a Latin word and on the other side, write it's meaning. Take a sharp, thin pen to do this. Here's what I mean:  One thing this picture doesn't show is that fact that you should number each corner. Put a "1" in the top left piece and a "2" in the top right, "3" in the bottom left and "4 in the bottom right. I made this puzzle to review for the National Latin Exam but of course any vocabulary can be used. As you can see, small words are best because you don't have a lot of space to work with. This works best as a partner activity. Hand out one puzzle to each pair of students. Make sure they move their desks adjacent to each other so that there are no gaps. Otherwise, pieces will fall on the ground and this will lead to stress in the completion. Next, students carefully cut up the puzzle along the lines. I hand out scissors to everyone and instruct the students to cut the puzzle in half first and then give half to their partner so that both partners can be cutting at the same time. Now be warned here - since the students know that the next step is to put the puzzle back together, a few groups may cut up the pieces and keep them in the row. That way, the puzzle takes only 20 seconds to put together. I actively go around and stir the pieces on the desk. Sometimes I ask everyone to switch desks. Here's what it should look like when it is cut up: The way to put together the pieces is to find the meaning of the Latin word. You may notice that the piece on top square says "Quis." Students need to find the piece that has "who" along the edge. I strongly suggest that you counsel students to use traditional puzzle strategy to piece this together. They should take out the corner pieces (the numbered ones) and then separate all the edge pieces. The edge pieces will have three words instead of four. They should build the frame first and then build the inside. Here is a puzzle in progress. A vocabulary puzzle of this size takes students about 30-40 minutes to complete. You can of course make a smaller puzzle by folding the paper less times and making bigger pieces but I find those puzzles take less than 10 minutes to complete that it's rarely worth the effort to set up. You will also find that your "puzzle stars" are often not your top students. Often my A+ students wind up staring grimly at a half completed puzzle while a pair of students who struggle a bit have already completed the puzzle. To keep everyone on task, I usually offer a small prize for the first team to finish the puzzle.

Here is a link to the Omnia folder. The card and board game folder is in this main folder.

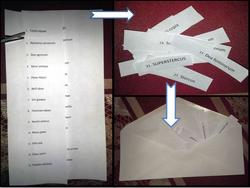

This is another game that has been around for a while. I believe Linda Kordas dubbed the Latin version as Stercus. In the Ecce Romani series, Stercus or manure plays a pivotal role in Chapter 21 entitled "Murder." Students using the Ecce Romani series rarely forget that word. It is, as I think you will see, an apt name for the game. This is an excellent small group activity that can be used to reinforce many different things - phrases, vocabulary, verb tense, prepositional phrases - pretty much any information that can be broken down into small chunks. Students play this game in small groups of about 3-5 students. Each student in the group competes against the other students to see how many correct answers they can pull out of an envelope before pulling out a STERCUS and losing all their points. Pre-game Preparation The first step is to create a Stercus worksheet. This contains 30 numbered questions that students must answer -perhaps 30 verbs in several tenses to translate or perhaps 30 short phrases with prepositions. It could even be 30 vocabulary words. I like to create this worksheet in 2-3 columns because it makes the second step easier. The next step is to take a copy of the worksheet and cut up all the questions into small pieces until they look like the fortunes from a fortune cookie. In addition to the questions, you need some pieces that say STERCUS and one that says SUPERSTERCUS. The number of pieces that say STERCUS is important. You want the STERCUS pieces to be about 15-18% of the total number of questions. This means that if you have 30 questions, you want to put in 6-7 pieces that say STERCUS. No matter how many question pieces you have, you only what one that has SUPERSTERCUS. You then put all these pieces into an envelope. You repeat this step for as many groups as you will have playing the game. If you have 20 students, I recommend that you make 5 groups of 4 students and make 5 STERCUS envelopes. If you can see from the helpful "how-to" diagram, I cut the worksheet in half vertically first and then lined up the columns and snip both columns of questions up at the same time. This is easy to do when the questions are in two or three identically spaced columns. It's not necessary, just a way to save some time. Give each student a copy of the uncut up worksheet and have them write the meaning of the phrases. Review the correct answers with the class.

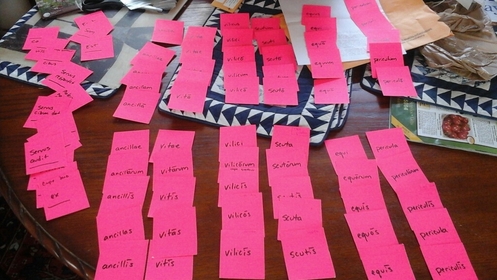

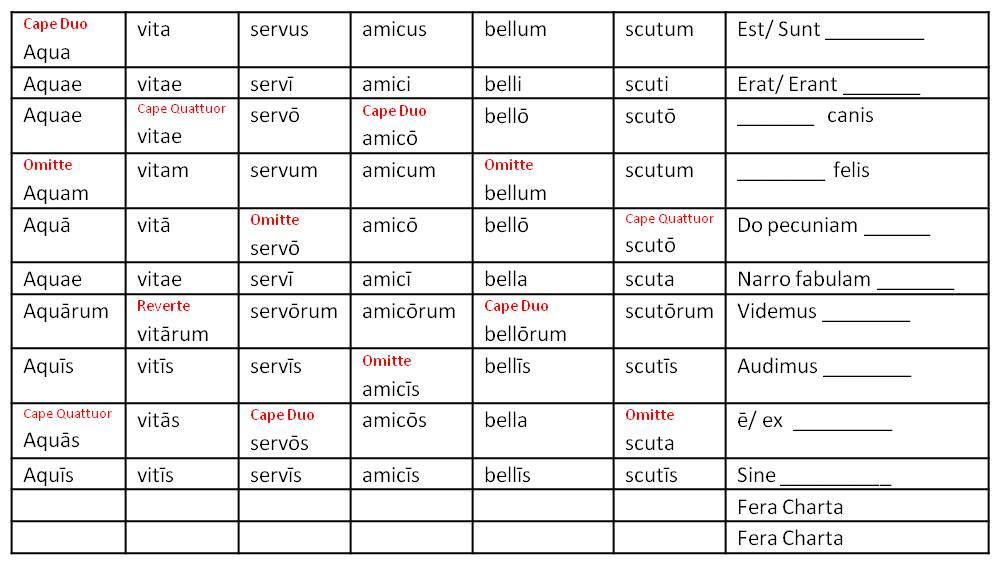

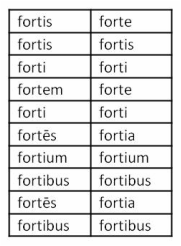

How to Play the Game Now you hand out one of your pre-made envelopes to each group students of 3-5 students. To play the game, each group sits together. Each group appoints a scorekeeper to keep track of the points earned by each student in the group. The first student to play reaches into the envelope and shuffles the pieces. Without looking, he or she pulls out a piece, reads the phrase and says the answer. The rest of the group checks his or her answer against their corrected worksheet. If the player has the correct answer, the scorekeeper awards the player a point. He or she leaves the piece outside of the envelope and pulls out another. Again, the player reads the question and his or her answer aloud. If the player does not have the correct answer, then they do not get a point. They can however continue to pull out pieces. In middle school, I limit students to 4 pieces per turn. However, in high school, I let students pull out as many pieces as they wish. Here's the fun part. As the player pulls out more questions, he or she may score more points but if he or she pulls out a STERCUS, then they lose all their points from the round and their turn is over. Should the unlucky player pull out a SUPERSTERCUS, their turn is over and they lose all the points not only from this round but all previous rounds. Eheu! Once a player's turn is over, they put all the pieces back into the envelope and hand it to the next player who repeats the process. The winner is player who has the most number of points when the game is over. I generally let students play about 20 minutes which is about 3-4 rounds. The unpredictable nature of probability makes this game entertaining. Some students will find that they rarely get to answer more than two questions correctly before pulling out a STERCUS and others will pull out multiple questions for several rounds without ever losing any points. "Why do I ALWAYS get STERCUS?" They ask me. What can I say? The inscrutable nature of luck has baffled philosophers and scientists since the dawn of recorded history. Ask me something easier - like how to use indirect discourse within a subjunctive clause. The purpose of this card game is to reinforce students' understanding of case and which endings indicate each case. I've always found this a pretty important idea in Latin no matter what textbook I'm using. This game follows rules similar to the popular card game, Uno. Instead of playing cards that have the same color, players must follow case. If one person plays a card with a dative ending, then the next player must play another card with a dative ending. If he or she cannot and is not able to change the "case," then he or she must draw from the discard pile until he or she finds a suitable card. To change the case in this game, a player needs to put down a direction card. Each direction card contains a short phrase which needs a specific case to complete the phrase. I understand that the Cambridge series offers a similar game with similar rules without direction cards. Personally, I like the idea of using the direction cards because it reinforces the idea of the kinds of phrases that take each case. However, your mileage may vary. This is a good game to use when everyone has memorized the noun chart, at least first and second declension. All students should be familiar with the use of the cases. This game is not as difficult as Latin Poker. In general, students towards the end of Latin I or taking Latin II can play this game with relative ease. How to Make an Unus Deck: To make an Unus deck, you need to find some 3x5 index cards and cut them in half. You will need about 80 cards. Here's a helpful crafty demonstration of how to do this: Now below see a picture of an Unus set laid out on my dining room table. Unfortunately, the table was already full of other projects so it's not the greatest picture. Don't worry, I will detail exactly what cards to make. Okay, now below see a more helpful chart of all the cards you need to make for this game. Basically, you need 2 feminine first declension nouns , 2 masculine second declension nouns and 2 neuter second declension nouns all declined on cards. You will also 10 direction cards and 2 "wild cards." In the top right hand corner of any three cards, you need to write "Cape Duo." On the top right hand corner of three different cards, write "Cape Quattuor" and on a third three, write "Omitte" and a fourth three, write "Reverte." I will explain later what this is. Here's what the set looks like: The last column contains the direction cards. The " _________" is to indicate what case would fit the phrase. The first two are nominative direction cards. This means that if a player puts down "Est/ Sunt ___________" then the next player needs to play a nominative card. It is what fits the phrase "There is or there are _________." The player can play a singular or plural nominative card in any gender. The next two are genitive direction cards, "_______________ canis" indicates that this is someone's dog - a possessive genitive. The following two are dative direction cards followed by accusative direction cards and then ablative direction cards. It's a good idea to write all these phrases on the board before playing so that students are familiar with what case the direction cards indicate. Fera Charta indicates a "Wild Card." (Yeah, I know - I like fera anyway) When a player plays this card, he or she should declare what case should be played. The small words in red on some of the cards indicate that if this card is played, the following action should be taken: Cape Duo - Take two! Cape Quattuor - Take four! Omitte - Skip the next player Reverte - Reverse direction of play. Seriously, you don't need to use these words if you prefer other first and second declension nouns. It doesn't matter what words you choose as long as you decline them on the cards. You also don't have to write the Cape Quattuor etc. on the words that I have written them on. As long as you have 3 of each and 12 in total, it will work fine. How to Play: One Unus deck should be used between 3-5 players. Give each group of players a deck. After shuffling the cards, the dealer of the group should deal out 7 cards to each player. Put the remaining cards in the center of the play area. Choose someone to go first who has a Direction Card or a Fera Charta in their hand. If they start with a Fera Charta, the player needs to declare what case he or she wants played. Each player can only play one card at a time. The next player has to follow case. If the player does not have the correct case, then he or she must draw from the pile until he or she draws the correct case or a Direction Card or a Fera Charta. If they draw either of the last two, then they can change the case to something else. If someone plays a card with an extra direction such as Cape Quattuor, then that direction affects the next person to play. In this case, the next person would have to draw four cards. The player drawing four cards or two cards doesn't get to put any down. In the case of Reverte, then the next player is now the last player because the direction of play has changed. In the case of Omitte, the next player's turn is skipped. Play continues until one player succeeds in getting rid of all their cards. The game generally takes 20-30 minutes to play. Third Declension Adjective Addition If your class is familiar with how to pair third declension adjectives with first and second declension nouns, you can add a set of third declension adjectives to the deck. This will increase your set by 20 words and also increase the difficulty of the game. Here is an example of a third declension set to add. Of course you can use any third declension adjective. Like the above chart, each box signifies a card. I would not advocate adding more than 20 more adjective cards. Otherwise, it will unbalance the deck. The rules concerning adjective cards are as follows: A player can play an adjective at any time even if it is not their turn if it matches a noun that has just been played. A player may also play more than one adjective if it matches the noun that has just been played. A player can only play an adjective if it is followed by a noun. If a player want to put down an adjective during their turn, they must have a noun in the correct case or they must draw from the deck. A player who plays the wrong case of the adjective must as a penalty, draw two cards from the deck.

Final Thoughts If you've followed this blog to the end, it's probably dawned on you that making a set of Unus cards requires a fair amount of writing and cutting. If you have a class of 20, you need to make 5 decks so that everyone can play in small groups. The good news is that if you've done it once, you can reuse the cards from year to year. Unus is a great emergency lesson plan. Class cut in half by fire drill? Pull out Unus! Half the class gone to the band room for extra unannounced concert rehearsal? Let's play Unus! There's something about a card game that creates a special camaraderie. I love to deal myself in as a player in these games. Anytime you can interact with students where you are not standing in front of the board, good things tend to happen. So I urge you, cajole you - make some Unus sets. This game has been play tested to death. It instructs, enhances personal relationships between members of the class and even more importantly create positive and long lasting memories of Latin. |

- Salvete Omnes!

- About Me

-

The Stuff is Here

- Beginning Activities

- Card and Board Games

- Kinetic Activities: Get 'em out of their seats

- Mad-libs for All Levels

- Miscellaneous Low or No prep Activities

- Movie Talks!

- Stories Not in Your Textbook

- Stuff for Advanced Students

- Teaching Case

- This I Believe

- White board Activities: Winning.

- Writing in Latin with Students

- Mythology RPG

- Songs

- Quid Novi?

- Links!

- TRES FABULAE HORRIFICAE

- LEO MOLOSSUS

- OVIDIUS MUS

RSS Feed

RSS Feed