|

Rules for Hero Creation

The rules of how to create a hero are contained in the Hero Creation Packet contained on the Hilara Google Drive. They are pretty clear - my students have always been able to create heroes following these rules. Rules for the RPG: First of all, these are more like guidelines rather than rules. This is not chess. It is a dynamic story that is constantly changing and the rules change with them. The modus operandi is for the Muse to read the RPG adventure ahead of time. When playing the game, he or she reads aloud the text in bold to the group and asks them what they decide to do. This is pretty fluid and the muse often acts as a referee discarding terrible ideas - "We build an airplane and fly out of the window!" and encouraging good ideas. "We get our weapons and creep down the stairs." The basis of the gaming system is a 20 sided die. This is one of 5 dice that you will need but it is the one you will use the most. Students create heroes that have characteristics. These are: strength, intelligence, dexterity, charisma, courage, endurance and comeliness. These are all clearly detailed in the Hero Creation packet. Many times, to determine whether or not a hero can accomplish a task, the player will roll a 20 sided die and hope to roll under the points they point in that characteristic. WHAT? Let me give you an example: Your hero has 12 points of dexterity. He sees an enemy and attempts to attack the enemy with his sword. To determine whether or not he hits the enemy, the player rolls a 20 sided die and if he rolls a 12 or UNDER his dexterity score, then he makes contact. If he rolls over, he misses. Here's another: Your hero has a courage score of 5. Your group sees a ghost in a dark forest. To determine whether or not the hero is able to stand his ground, he rolls the 20 sided die. If he rolls under his courage, he faces the ghost. If he rolls the same number or over, he runs away in fear. Not all the characteristics translate to this kind of roll. If a character has a high intelligence, he or she will have more skill points than one with a lower intelligence. How many extra skill points is described in the character creation packet. Students can choose skills that their characters have from a list of skills in the Hero Creation Packet. On the Hero Sheet, players list their skills as the number of points that they put into that skill. Like characteristics, the maximum points they can put into a skill is 20. Unlike characteristics, they don't have to put points in all skills. Sometimes a character will need to accomplish a task that requires a certain skill. Let's say, the groups sees a frightened horse wandering in the burning city. Can they capture it? Does anyone in the group have Equestrian skills? If so, they should make a roll on a 20 sided die. If they roll under the the number of points they put in that skill, then they successfully capture the horse. If not, then the horse runs away. When do I make these rolls? The RPG adventures explains when to make all these rolls. That doesn't mean that the muse can't add other rolls into the game when the characters go off script, as they will do frequently. How do you do play out combat in the game? The combat sequence is explained in the drive on the sheet: Combat Sequence. you should photocopy that and hand it out to your muses to follow. Basically, this is how it works: Characters wishing to attack an enemy must make a successful dexterity roll (Use a 20 sided die and roll) . Then, if the character makes a successful attack (by rolling under their dexterity score) , damage is determined. Damage is determined by rolling one of the other 4 die. The greater the strength of the character, the more damage they can do. All of this is explained in the Hero Creation Kit. But let's say, the character has a strength of 16. In that case they roll an 8 sided die. Let's say, the character rolls a "6." In that case, he does 6 points of damage. These 6 points are subtracted from the enemy's life points. Players can lose life points too when enemies make a successful attack against them. All the statistics for the various enemies attacking are given in the various adventures. Players roll for themselves and the muse rolls for the enemies. Suppose a character loses all his or her life points? Then they are dead. There is no cure for dead. That character is retired and the player must make a new character. The player is out of the current adventure but the player's new character will be brought in on the next RPG. In general, most players can avoid having their characters killed by working cooperatively with the group. Characters most often die when they go off on their own and do something stupid - like attack a Cyclops. I find in general that if a character dies, the other members of the group are glad to be temporarily rid of that player. The player then tends to reflect on his or her behavior and is usually more cooperative once they are brought back into the game during the next adventure. It's boring to be dead. Players with dead characters usually try to avoid that happening a second time. Can characters get back life points that they have lost through combat? Yes - the most intelligent character of the group should take on a number of healing skills. Once there is a break in the action - after a battle for example, the character can employ his healing skills to give back character's life points. Characters may not take back more life points than they originally started with. Also, all characters "heal" in between RPG adventures. So characters that had lost life points during the second RPG are healed back to full strength at the beginning of the third.

0 Comments

Here is the link to the Omnia folder which contains the links the mythology Game. The mythology game is in two folders - RPG I and RPG II. RPG one contains information on making characters and RPG II contains the actual adventures.

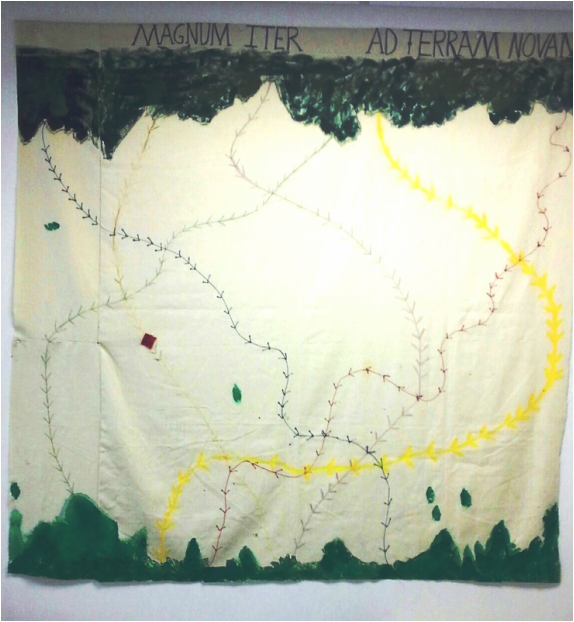

In between each RPG adventure, the focus switches from the RPG to the game board which represents each team's progress sailing from Troy to found the new homeland on the other side. (See picture below) The first team to reach land on the other side will be the conquerors of all others - destined to rule over cities created by the other teams. In other words, they fulfill Vergil's destiny for Rome. The game is over when the first team touches land so practically speaking, they just get bragging rights but that's almost as good.

Each team rolls dice and moves their boat, which is represented on my board by a felt square along a line. Each group makes two rolls. They first make a "Ship Event" roll which is made by rolling two six sided (regular square) die. The Ship Events List is in the drive. I usually pin it up next to the board and have a class member read off what happens as each group rolls. The events are listed from worst to best. The best event is 66 and the worst event is 11. Note: It is useful to determine which die will determine the one's place and which will determine the ten's place ahead of time. I use a colored die for the ten's place to avoid any argument. The event roll does not determine but may impact the number of squares the group may move. For example, if the group rolls snake eyes, then no one goes anywhere due to a terrible storm. There are less dire consequences such as a hole in the sail etc. as well as some helpful events - finding food, water or a strong wind. The second roll determines how many spaces the group moves on the board. See the "Ship's Log" worksheet in the Hilara drive. The die that the group rolls depends upon how many rowers the boat has. This is explained on the worksheet. On the log is space where you can jot down all the events that happen to each team. I find it useful since some events impact the next week's progress. I used to ask students to keep the log but I eventually found it simpler if I just wrote it down as they rolled. We move the boats on Fridays at the end of class. Sometimes each team moves once - sometimes twice. I usually reserve about 10 minutes for this activity. Who should roll for the team is usually a hotly contested topic. Everyone wants to find the "luckiest" roller for their team. By the end of the third adventure, students should be within 15 spaces of the end. If they are not, simply advance each boat the same number of spaces until they are. Below is a picture of my "Map" that hangs on the wall in the back of my classroom. There are 40 spaces in between the top, (the starting place) and the bottom - the terra nova. Each episode begins with a message in Latin in which students learn the important task that they must accomplish in order to be successful in the adventure. The messages are given either by the gods or by ghosts. It is not necessary to do the translation to play the RPG. If you prefer, you can impart the message in English.

RPG #1: Escape from the City: This adventure most closely follows Book II of the Aeneid, specifically the part where Aeneas describes his last night in Troy. In this adventure, students will have many encounters similar to Aeneas. They will meet Hector's ghost (whose message in Latin they must translate). They will witness Pyrrhus' encounter with Priam, run into a group of Trojan fighters dressed as Greeks and of course, Helen. At the end of the adventure, Jupiter will draw the veil from their eyes and show the players how the gods are actively destroying Troy. I designed this adventure to give students' the sense of the conflict Aeneas feels between fighting to save his country and fleeing. It is, like all of the RPG episodes , not a carbon copy of Aeneas' experience but there are many parallels. RPG #2: Island of the Lotus Eaters: This episode begins with a translation in which the gods speak to the group and tell them about the island and their mission to find the Sibyl. They meet the Lotus eaters which is always highly entertaining. It always interest me to see which characters decide to eat the Lotus and which don't. Besides the Lotus eaters, the group meets the Sibyl (from Book VI) and must find the golden bough for their trip to the underworld. They also encounters a love-sick nymph and collect much needed supplies for the journey ahead. RPG #3: Island of the Cyclops: This adventure combines many different encounters contained in Book III of the Aeneid, specifically Aeneas' run in with the Harpies, the ghost Polydorus, and of course, the Cyclops. Polydorus whom the group meets first in the adventure describes his sad fate which is the translation for this adventure. Artistic liberties have been taken to contain these encounters on one island adventure but I believe that it captures many of the Aeneid's darker episodes. Gods, Help Us! - In between episode 3 and 4, I usually have the students do the only graded assignment for this project. The guidelines for writing the prayer are in the Hilara drive. Each group must write a prayer in Latin to the gods and ask for the things they need to make it on the final leg of their journey. I usually give homework credit for each completed prayer and write a note as one of the "gods" that explains how many spaces they get to move or how much food and water they receive. Sometimes in the case of a particularly egregious prayer, the "god" upbraids them for their careless grammar and sends a thunderbolt to break apart the ship. Despite the fact that everyone is aware that I am all the gods, the students never question the judgement of the "gods" even when it's harsh. They have no problem however arguing with the "teacher" about grades or credit. If only the "gods" could run parent/teacher conferences... RPG #4: Journey to the Underworld: The translation in this episode also begins this adventure. The gods tell the group about the dangers ahead and explain that they must find the Furies. This episode is taken from Book VI of the Aeneid. In this episode, characters will run into many famous inhabitants of the underworld not mentioned in the Aeneid but certainly part of Greco-Roman mythology. Characters encounter Tantalus, the Danaids, and Sisyphus. They must get past both Cerberus and Charon. Like Aeneas, the characters get a brief glimpse of their future glory. However, this glimpse is designed as a riddle that they must solve in order to escape the underworld. Each group is faced with the ghost of a future enemy of Rome and must "conjure" the future Roman hero who defeated that enemy. Students will need to do some brief in class research to determine that they must conjure a specific spirit and which spirit that is. The teacher, playing the part of the "Furies" gives them hints. However, too much conversation with the Furies may drive the characters to madness. For more specific information about the role of the teacher as Furies, read The Teacher's Guide to RPG #4 in the drive. Once students have escaped the underworld, they again move on the board to the finish line. Before embarking on a mythology role-playing game, students need a working knowledge of Greco-Roman mythology. As a minimum, students should be acquainted with the main pantheon of gods and domains. Beyond that, these myths are a good starting point.

The Odyssey: Students need not know much about this book. I tread lightly here because students read the entire book in ninth grade English. It helps if they understand the following:

The Trojan War:

The Aeneid : It is not necessary that your students know they entire story. Since the RPG is loosely based upon the journey of Aeneas, they should have familiarity with the following ideas.

Students need not be experts. Due to the popularity of the Percy Jackson books, they will probably already have familiarity with of these many monsters and scenarios. However, the more comfortable students are with the mythological world, the more vivid the RPG will be for them. They need to know that strangers should be treated as guests, gods should be respected and never challenged, and most importantly, fate is fickle and fairness cannot be expected. How you acquaint your students with the myths is up to you. Over the years, I have done a number of different projects to teach mythology, but by far, the best vehicle I have found for teaching these stories is simply to tell them orally. I tell one myth every Friday and the class loves it and more importantly, remembers it. Goal

Groups of adventurers must escape their burning city, get into boats and sail across the sea to found a new city. The first group to land on the opposite shore is the "Victor," the founder of the city that will conquer all others, subjugate the proud and protect the meek. Game Parts RPG Adventures - 4 in all which are spread out over a course of 6 weeks (see time line under "Project Timeline and Dice" for further details). These include: Escape from Burning Troy, Adventure on the Island of the Lotus, Adventure on the Island of the Cyclops, Challenge in the Underworld. All RPG's adventures are in the Google drive. Game Board A board that can be projected on the wall using PowerPoint that charts the groups progress from one side (Troy) across the sea to their new homeland. Roll dice and chart the students' progress across the board. This is also in the Google drive. NOTE: The game board is not there yet. I need to collaborate with a better artist to create this. The game board is simply 40 spaces in between the top "land" and the bottom "land." For the time being, you will have to make your own board. See "Moving the Boats" for a picture of the one I made for my class. Now it's time for a break down.... Step I: Teacher puts the students into groups of 5-7 students appointing one student to be the Muse. The muse is responsible to read the adventure to the rest of the group and guide them through the adventure. In gaming terminology, this person is the dungeon master or Game master (GM or DM). The muse should be a student who reads well and is a leader. They need to be responsible to do the reading required for the adventure ahead of time and their class attendance should be good. It is a good idea to talk to potential muses ahead of time to make sure that they are willing to take on the responsibility. Most often students are honored to be asked but occasionally, I find a student who does not want to do it. I find it is a good idea to put students in groups with their friends for this activity. I also like to balance shy students with more outgoing students. Step II: Teacher announces the groups to the class and explains that everyone will be playing a group of adventurers who are on a quest to found a new city after their city has been destroyed by the enemy. These adventures are all semi-divine, a la Hercules or Perseus and while not immortal, will have skills beyond the ordinary person. (Yes, very much like Percy Jackson to answer to inevitable query.) I announce who the muse will be in each group and explain that this person will lead the adventure and will have greater powers than the rest of the group since they will have control over certain aspects of the story. It is never a good idea to anger the muse. Step III: Teacher puts students in their groups and hands out the character creation packets. Teacher also hands out list of Latin agnomens to help name heroes. Students fall on the packet like hyenas on a wildebeest carcass. It is a good idea to remind students that they should create characters that have a variety of abilities and skills. Step IV: Teacher meets with the muses after school or during a study hall and leads the first adventure while they play the character. Teacher then hands out the first adventure to the muses and tells them to read it and then lead the adventure with their players. Step V: Students complete first adventure - "Escape from the City." First part of the adventure is a translation where Hector speaks to the adventurers and explains to them that they must leave the city, and what they must do before they leave. All of this is on the Google drive. Step VI: Students move their "boats" from the starting position (Troy), roll dice and move out into the open water. Move the boats by rolling die 2-3 times before starting the next adventure. The game board for this part is not yet on the drive but it's not difficult to recreate. More about moving boats in other blogs. Step VII: Students complete the second RPG - which consists of a translation and an adventure on the Island of the Lotus. Step VIII: Students get back into their "boats" and roll die to move the pieces further down the board. Step IX: Students complete third RPG - Island of the Cyclops. Again, they must complete a translation before beginning the RPG Step X: Students roll dice and move their boats closer to the finish line. Step XI: Students complete the final RPG, Trip to the Underworld and immediately after the group solves the final puzzle and gets out of the underworld, they roll dice and move their ships. This adventure is different from the other three since in the other three, the moving of the boats can be done the next week. In this adventure, which ever group emerges from the underworld first gets to move their boats immediately and sometimes two or even three times before the other groups solve the puzzle. Step: XII: One boat lands on the opposite shore first. Victory! The winning team usually jumps around, hugging each other, singing disjointed renditions of Queen's "We are the Champions" and the game is over. Activity: Time required (approximately)

*Character creation 1- 1.5 hours *RPG adventures (4 total) 45 minutes each *Translation (4 total) 20-30 minutes each Moving the "boats" 5-10 minutes per time (You will need to move the boats approximately 6x) The absolute minimum: Create characters, do the first RPG = approximately 3 hours (the activities that are starred) The whole program: If you wish to adopt the whole program, I suggest that you do this the following way: Have students create characters the Thursday before February break and finish the process the next day, on Friday before vacation. Explain process the Friday after you get back from vacation and then do one of the 3 RPG's every other week. That will take the game approximately 6 weeks to finish. It is likely that you will need to skip some weeks due to vacations, field trips etc. In my experience, the game usually draws to a close 8- 10 weeks after we start. The fourth and final adventure happens towards the end of school often during the last week of school. It is a great activity to end the school year. Dice are rolled to determine the outcome of combat - who hits who and how hard. Dice are used also to add and subtract life points from characters, as a result of combat and thus can determine the life or death of that character. Dice rolls move the ship from one side of the board to the other and determine events on the ship.

The exact times in which to use dice and how to use the dice are detailed in the adventure. The way that combat is determined is also listed in the Guide for the Muse. If you haven't done this before, I know it sounds complicated. But trust me, it's not as difficult as it sounds and the kids will get the hang of it really quickly. The dice above are the dice necessary for this RPG. Each group needs this set: one 20 sided die, one 10 sided die, one 8 sided die, a traditional 6 sided die and one 4 sided die. In the case of the 4 sided die, the number to read is the one that's all the same, usually the one on the bottom. Sets of these dice are easily acquired from the local gaming store in your town. I use the roll of the dice to help students understand the role of fate in mythology. Fate is unknowable and unwavering. It is often unfair - independent of a character's good or bad acts. It answers to no one, even Gods. Of course this fact has not prevented numerous heroes and gods from attempting to alter or escape it. There are numerous myths that illustrate this point. However, sometimes the RPG makes this point even clearer. One year while leading a class through the game, one group in the class seemed to have the advantage. They did extra homework assignments to advance their group and the gods (myself) had rewarded them handsomely. They had solved all the puzzles quickly with a minimum of bickering. They had escaped the underworld and were in sight of their new homeland. But then tragedy struck. They rolled dice and instead of sailing into harbor, they hit a terrible storm and then unbelievably, another, and then a third. While this group was struggling to put the pieces of their boat together, a second group, initially very far behind also rose out of the underworld and sailed smoothly into harbor, establishing their homeland first and winning the game. Deeply disappointed, the first group asked me, "Why? What happened? What did we do wrong?" I shrugged. "You were not fated to win," was all I could offer. Fate is a cruel master - unyielding and unpredictable, deaf to the pleas of mortals and gods alike. Of all the things that I have done in the classroom over the past 20 years, this has been the greatest success. I can say this confidently because I have play tested the mythology RPG with students taking Latin I in grades 7-12 for the past ten years with several different textbooks. During the time that I've done this activity, students have made their beleaguered parents reschedule doctor and orthodontist visits rather than miss the mythology RPG. They have wept when told that they could not play until their homework was completed. (Yes, that was awkward - not to be desired.) They often groan when the bell rings, then beg to stay through lunch. Recently, during an unannounced administrative walk-through, the students showed up early, put their groups together, distributed the material and began the RPG without me. I had learning targets, success criteria, and a "bell-ringer" activity ready to go but it seemed pointless when the class was engaged and on target before I had even entered the room.

I know it sounds ridiculous, hardly like school at all. But really, after ten years of play-testing, I can say confidently, this is not a fluke. It engages, it instructs and it really works that well. What is an RPG? There are many types of role playing games. The kind that I use to teach mythology is called a "table-top" role-playing game. It is called that because it doesn't use a computer or costumes or any sort of live action. The players sit around a table. They each play a character and a sheet that details the characteristics and skills of that character. However, the majority of the action happens in students' respective imaginations. The game master, or as I like to call the leader - the muse, tells a group of 4-6 players a story. As the muse reads the story, he or she pauses frequently to ask the characters what they are doing in this situation. The characters, argue, discuss and then tell the muse their plan. Based upon what the characters say, the muse tells the characters what happens next. The story can change dramatically depending upon the choices that the players make. Dice are rolled to determine the result of chance encounters or combat. Both the characters and the muse roll dice at different times to determine certain outcomes. An RPG is a bit like one of those old fashioned "Choose your Own Adventure" books where you read until the author gives you three choices and depending upon the choice you make, you turn to a different page in the book and the story continues until you make another choice. This way you can read the story three times and have three different outcomes. Here's the thing though - I never liked those books very much. The adventure always seemed to fall flat. They never succeeded to make me feel like I was part of the story. An RPG pulls the players into the story, binds them together and sucks away time. If you have played a table-top role playing game as a teenager, Dungeons and Dragons or any of its many derivatives, then you know what I am talking about. If you haven't, you are probably hesitant. It sounds complicated and corny. I understand. However, this is where you need to take a great leap of faith. Read on. It will work. Okay, but how do you grade this project? That's an easy question. You don't. You don't grade any of it. Students will eagerly participate in the RPG despite the fact that it does not contribute to their overall average for class. In fact you can use their participation in the RPG to get them to do more graded work or do the graded work you demand with more care. I don't even give extra credit to the student who is the "Muse" and must read the adventure packet ahead of time for the group. I used to, but honestly, the honor of being the muse was a far greater gift than any extra credit I was offering. There is one graded assignment in the Google Drive. It is a prayer to the Gods that I ask each group to write in Latin in between the third and fourth RPG adventure. For following the guidelines of the prayer, the teacher gives credit. For writing a comprehensible and flattering prayer, the gods give a reward. Students are always far more interested in what gifts the "gods" may give than the credit. So it's fun but what are they actually learning? Good question. They will practice the following:

They will gain:

No doubt you can find these terms in your standards or frameworks, phrased in more appropriate educational jargon. Beyond these skills, the greatest thing you will garner from your students is MOTIVATION to do the other tasks you ask them to do. In order to play the RPG, in my class, students need to have completed the homework the night before. Any student who didn't complete the homework to my satisfaction works in an adjoining room or at the back table until it is done. My homework completion average on game day hovers between 90-100%. Sometimes I award bonus points of wind motion, magic swords, or life points to homework that is done well or to any group where everyone has done the homework. Once, struck down mid-day with a fever and too exhausted to teach, I photocopied a translation, handed it out to the class and told them that any group that finished it would receive 20 additional skill points. I then collapsed at my desk and braced myself for the din I expected to ensue since I didn't have the energy to properly monitor the lesson. Miraculously, there was complete silence except for urgent whispering and scribbling. I looked up. Everyone was working furiously. Homework credit? Test review? Not important to all ninth graders as I am constantly shocked to discover. But skill points for their hero - that mattered. Another bonus is the fact that these rewards have no monetary cost. Candy is strictly verboten in all schools. Pencils and stickers with Latin mottoes are great but they are expensive and no district that I have worked for has been interested in reimbursing me for student reward trinkets. Also, as one administrator asked partly in jest, "What am I going to say to a parent that calls and complains that you didn't give their child a magic sword?" "Nothing." I told him. "You will say nothing because no parent is going to call and complain that their child's imaginary hero didn't get an imaginary reward for an activity that doesn't factor in their grade." He chuckled. I have curriculum to cover. How much time does this take? The entire project from start to finish takes about 8-10 hours. If you can set aside 8-10 hours over the period of a year, you have time to do this. For more about exactly how long each segment takes, see project time-line and dice. In addition, it will save you time because it will motivate students to do things on their own that would have taken up class time. Will this work with MY students? Good question. Here are some questions to help you decide. If you can answer affirmatively to all of these four questions, then I am confident that mythology role-playing will work in your classroom as well. 1) Do you teach teenagers - ages 12-18 taking a Latin I class? 2) Do the majority of your students enjoy stories about mythology, heroes, quests or magic? 3) Can you find one student for every 5 that you have in class who can read aloud fluently, confidently and can be relied upon to read about 10-15 pages on his or her own over a course of 3 days? 4) Can your students work in small groups without bullying each other? Now by this I mean, without seriously making each other miserable, not causing some frustration or disagreements within the group. The latter is the more normal consequence of teenagers working together while the first requires adult intervention. If the answer to these questions is "yes," then this will be successful with your students. It is NOT necessary that you use a certain textbook or method of instruction to do this activity. It is NOT necessary that your students be familiar with RPG's or that they have played any role playing games before. However, I'll also be willing to bet that you have at least 2 or more students who are very familiar with this gaming format. When you tell them that they are going to be doing an RPG, their eyes will widen and your coolness factor will increase tenfold. |

- Salvete Omnes!

- About Me

-

The Stuff is Here

- Beginning Activities

- Card and Board Games

- Kinetic Activities: Get 'em out of their seats

- Mad-libs for All Levels

- Miscellaneous Low or No prep Activities

- Movie Talks!

- Stories Not in Your Textbook

- Stuff for Advanced Students

- Teaching Case

- This I Believe

- White board Activities: Winning.

- Writing in Latin with Students

- Mythology RPG

- Songs

- Quid Novi?

- Links!

- TRES FABULAE HORRIFICAE

- LEO MOLOSSUS

- OVIDIUS MUS

RSS Feed

RSS Feed